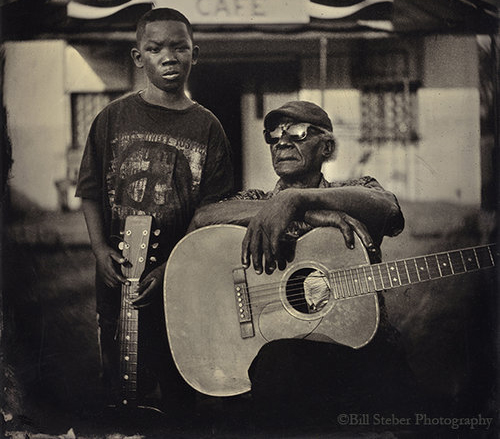

A clay skull sat on the shelf, its jaw filled with what appeared to be real human teeth. To the left lay a full-size sculpture of a woman in a casket. Welcome to the home of legendary Blues artist Son Thomas.

In 1992, photojournalist Bill Steber—passionate about music, especially the Blues—was visiting Mississippi for an article and couldn’t pass up this opportunity to visit the home of one of his heroes. Son Tomas’s son, Pat, led Bill to the bedroom where Son Thomas sat on his bed smoking a cigarette, just returned from the hospital where he was receiving treatment for a brain tumor.

“As far as my creative life, that was the day everything changed,” Bill said. “Everything about him—his music, his being, his philosophy, his art—it was just such prime source material for the human condition and more authenticity than I had ever experienced in my entire life.” Bill knew he had to come back for a longer visit. Unfortunately, he would never get the opportunity. Just a few months later, Son Thomas passed away.

It made Bill wonder “who and what else was there that is in imminent danger of disappearing,” he explained. “It became kind of a primary obsession of mine to seek out as many of the people or cultural traditions that created the Blues in Mississippi that I could find, and that started what is now a 30+ year life journey.” Thus began his photographic chronicle of Mississippi Blues history.

Preservation and fading have been themes of Bill’s art and life. He grew up in the Nashville area during a period when iconic restaurants or stores that had been around for years were closing, seemingly a different one every day. He was very close to his grandmother, and he grew up surrounded by stories and photos of the past, steeped in tradition. Even before he started his photographic chronicle of the Blues, he was interviewing his older family members, trying to capture all their stories and memories of a way of life that no longer exists.

“You can’t go back,” he said. “That’s the thing that has always been a primary motivating factor when I’m like ‘Do I really want to drive eight hours to go to this event?’ Yes, because if you don’t—that’s it. It’ll go unrecorded… It may or may not be valuable in the future, but if you don’t get it in real time, that’s it. It’s like it never happened.”

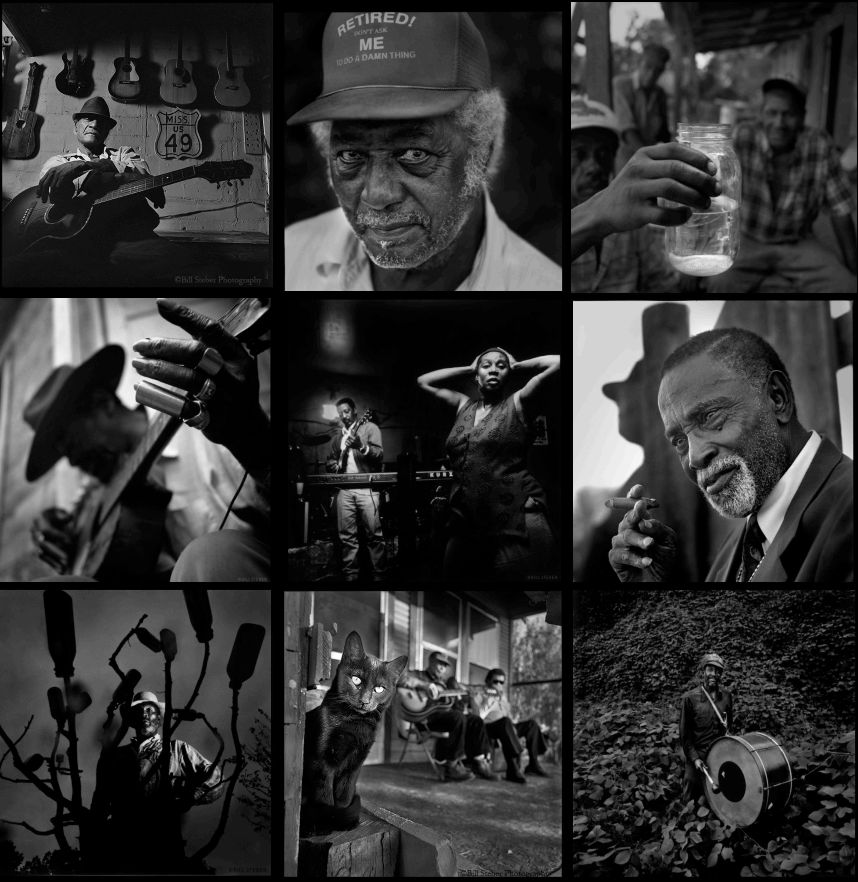

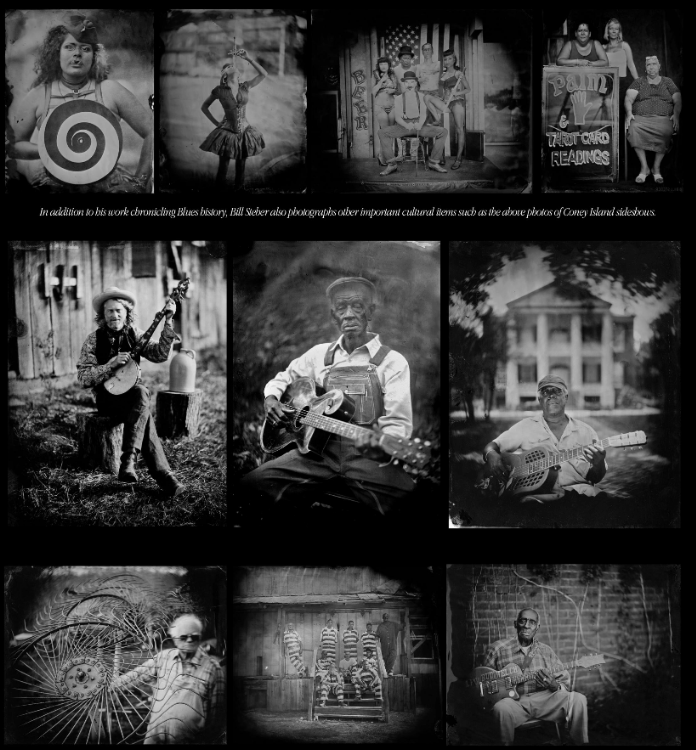

For more than 30 years, he has photographed “Blues musicians, juke joints, churches, river baptisms, hoodoo practitioners, traditional farming methods, folk traditions and other significant traditions that gave birth to or influenced the Blues.” He travels with an exhibit called “Stones in My Pathway” which has often been on display in museums.

He takes the pictures because he must. He takes them so that the music and traditions and people of the South won’t fade and be lost. To complement this theme, he often uses old photographic methods such as tintype which was common in the 1800s. Such pictures must be developed on the spot as they’re taken using potentially toxic chemicals. But you can’t deny the results. The aged quality of the photographs is a perfect complement to their subject matter.

Fading is something we all understand. Our bodies, our memories, even our very minds grow weaker as we age. Buildings crumble, nations fall.

Preservation, also, is an instinct we all understand, to hold the past close, to not let anything be lost, and to cherish tintype photographs of our traditions.

SteberPhoto.com