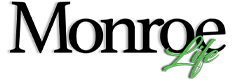

In July, 1945, the USS Indianapolis delivered the most powerful weapon that had ever been created—the atomic bomb that would be dropped on Hiroshima. Four days later, the Indianapolis was sunk by a Japanese submarine, killing 879 of the ship’s 1,195 crewmen, the greatest loss of life from a single ship in US history. Several of these crewmen were from East Tennessee, including Lt. Commander Kasey Moore and Lt. Commander Earl Henry from Knoxville. This is their story.

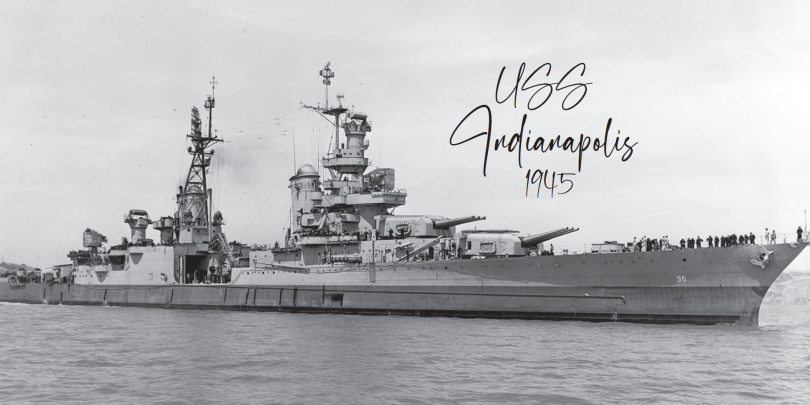

Last photo of officers of the USS Indianapolis before leaving California with the A bomb. Left to right front:

Commander Johns Hopkins Janney, Captain Charles McVay, Commander Joe Flynn, Commander. Glen F.

DeGrave. Back: Lieutenant Commander C. M. Christiansen, Lieutenant Commander Kasey Moore, Lieutenant

Commander Dr. L. Haynes, Lieutenant Commander Earl Henry, Lieutenant Commander Charles Hayes

It is unknown if Moore and Henry were close friends, but they did know each other before their assignment on the Indianapolis. Twelve years earlier, Moore had written an article about Henry in the Knoxville Sunday Journal, discussing Henry’s interest in taxidermy. The article notes that Henry planned on becoming a dentist and feared he would have to give up this hobby as, “People don’t want a dentist who has been handling birds working on their teeth.” Instead, Henry planned to take up bird painting, a hobby he would continue for the rest of his life. While the relationship between Moore and Henry is unknown, given that they were both officers of the same rank and were from the same town, it’s easy to imagine they may have been friends. Earl Henry joined the Naval reserve in 1940 before the United States entered the war. In late October of 1941, he married his wife, Jane. On December 7th, the “date which will live in infamy,” his parents threw a party to celebrate the marriage. The last person to arrive at the party announced that he’d just heard on the radio that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor.

Two months later, Earl Henry went on active duty. He would spend much of the war at Parris Island, South Carolina, and later at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, but after about 15 months at the academy, Earl Henry volunteered for sea duty, believing that he should take his turn. On July 25, 1944, he joined the USS Indianapolis as the ship’s dentist, a year and a day before the ship’s fateful delivery of the atomic bomb. Meanwhile, Kasey Moore entered the Navy reserve the day after Pearl Harbor. At the time, he was planning marriage with his long-time girlfriend, Katherine. However, those plans were put on hold by the war. Originally, he was given a safe assignment as a Navy Public Relations Officer in Nashville, but just days before he was supposed to leave, he announced to Katherine that he had applied for sea duty. She was stunned. “You are thirty-three years old!” she said. “You don’t have to do that!”

Katherine’s book, Good-bye Indy Maru, records his response: “I don’t want my grandchildren to ask some day, ‘What did you do in the great war, Grandfather?’ I don’t want to say ‘I fought the war with a typewriter in Nashville, Tennessee.’” In the end, Kasey and Katherine would marry on July 23rd, 1942, just a week before Kasey left to join the crew of the Indianapolis. Over the course of the war, Kasey would enjoy precious little time during shore leaves with his wife and his daughter, Mary, from his previous marriage. Each moment withthem was priceless.

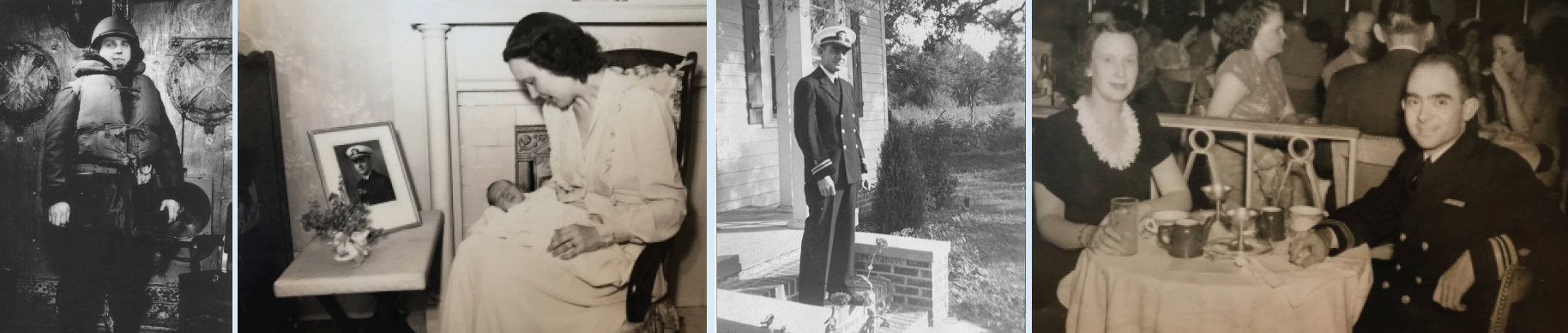

Left to Right: LCDR. K. C. Moore, damage control officer in special-made life jacket. The picture Earl Henry received of his wife and new-born son. Earl Henry. Earl and Jane Henry at dinner, Jane is pregant in this picture. Love letter on the back of the cardinal painting.

Kasey Moore loved his family very much, but soon he fell in love with the Indianapolis as well. Katherine had even begun referring to it as the “other woman.”“When I’m with her,” Kasey told Katherine once, referring to the Indianapolis, “the pain of my separation from you is bearable. When I’m with you, my heart is filled with joy and I wonder how I can ever leave you; but when I’m with her, she fills my mind. She is always there. You do understand, don’t you?”Katherine later wrote, “I did understand, but I was always wary of her.”Earl Henry was still painting birds at this time, but he’d slowed down after boarding the Indianapolis. Only two of Earl’s paintings from this time survive. One piece he mailed to his wife, Jane, as a birthday gift. A message scribbled on the back reads: “Happy Birthday, Jane- baby—I love you! Your sassy husband, Earl.” Sassy was one of his favorite words, and it is sprinkled throughout his many letters to her. The other painting, dubbed “American Eagle in the Pacific” depicts a bald eagle clutching a bleeding serpent, an American flag waving in the background.

During one shore leave, Jane became pregnant with their son, who they would name Earl Henry, Jr. Earl Jr., never met his father who died just over a month after his birth, but he knows more about him than many people who grew up with their dads. Earl Jr. has countless letters and postcards from his dad’s time in the war. He described what he’d put together about his father’s personality: “He was very obviously serious about birding, about dentistry,about family, but I don’t think he took himself overly-seriously. I think he had a lighthearted personality.”

In place of his bird paintings, Earl, Sr. began working on a painstakingly detailed model of the Indianapolis as a gift for his son. During one shore leave, Lt. Kasey Moore showed the model to his wife, Katherine, when she got to come aboard the ship. In her book, Katherine recalled, “The model of the INDY was the most beautiful thing I ever saw. It was about six feet long and perfect in every detail-rivets—‘life lines’ along the rails of dental silver, a tiny bell, the copper screen in the spud-locker door, gun turrets—everything that was top-side. The ship had been made of dental plastic and was as hard as tooth fillings. A peg in the bottom attached it to a base of polished teak.”

Since they both were from Knoxville, Katherine Moore offered to take the model home to Henry’s parents, but “Earl only smiled and shook his head,” saying that he’d take it himself when it was complete. In the end, the model would sink with the real Indianapolis. Perhaps it’s still within the wreckage, 18,000 feet beneath the ocean surface. Years later, Earl Jr. would look through the many surviving pictures taken aboard the Indianapolis for any photographs of the model, but he has never found one.

Around February, 1945, Kasey began having strange, foreboding feelings. In a letter to his wife, he wrote, “Several times of late I have seen you in the moonpath. You are always dressed in black and crying uncontrollably. You hold out your arms to me—and then disappear—” On March 31, 1945, the Indianapolis was struck by a Japanese plane in a kamikaze attack. In their book, “Indianapolis”, authors Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic describe the scene: “The blast shook Indy with seismic force… All over the ship, men fell against bulkheads or to their knees, doused in showers of grime and dust. Gear tore loose and clattered to the deck. The force of the blast ruptured portions of the deck, jacked others up at angles, buckled framing, and wrinkled Indy’s skin like the corrugated roof on a shed.” Nine men died in the explosion, and Earl Henry had to identify them by their dental records. Meanwhile, Kasey Moore, as the ship’s damage control officer in charge of hull integrity, examined the gaping wound the kamikaze strike had left in their hull. The ship limped back to Mare Island, California, for repairs, and the crew were given well-deserved shore leave.

Earl Henry travelled home while Kasey sent word to Katherine and his daughter Mary who quickly booked passage by train to join him. During this time, Kasey worked night and day repairing the Indianapolis, trying to fix it as quickly as possible, although there didn’t seem to be any particular rush. In the end, he would finish repairs just in time for the ship to be chosen to carry the atomic bomb, forever securing a place in history for the ship he loved. If he hadn’t finished in time, a different, slower ship might have been chosen, and perhaps the bomb would have never made it past the armies of lurking Japanese submarines and warships.

That day, Earl Henry received a letter from his wife with pictures of his newborn son. She had given birth prematurely, just five days after shore leave ended and Earl had had to return to the ship. Earl showed the pictures to everyone he could, and he sent a response beginning, “Baby angel, those two wonderful pictures came today, and I am delighted as can be over them!”

In that letter, on the back of his officer calling card, he wrote a note to his newborn son: “To Earl Jr.—if I make as good a Dad as your mother does a mother, you’ll be O.K. Love, Earl.” These pictures were the only time he ever saw his son in this life. Four days later, the Indianapolis was struck by a torpedo from a Japanese submarine. So dire was the situation that even Lt. Com-mander Moore, for whom the Indianapolis was “the other woman,” asked the captain if he wanted to abandon ship. The Indianapolis sank in just 12 minutes, and due to the secrecy of their mission, it took four days for the survivors to be rescued. Many would die in the water, but Earl Henry Sr. and Kasey Moore likely didn’t even make it that far. While their fates aren’t known with certainty, one fellow crewman believed Henry died in the initial explosion while reclining in his bunk. Moore was last seen in the mess hall, unwinding a fire hose in an attempt to save his beloved ship.

On August 15, Jane Henry received a telegram informing her that her husband was missing in action. As she wept, the church bells began to ring followed by shouts of joy, because right at that moment, news had arrived of Japan’s surrender. Their wedding celebration had occurred the day Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, and now Jane had learned of her husband’s death on the exact day Japan surrendered. Their marriage history had traced the timeline of the war. For Katherine and Mary, the news was equally bitter. Mary’s biological mother, Kasey’s first wife, had abandoned her years ago, and now she’d lost her father too. Katherine’s marriage had been cut tragically short, and

her husband was now buried within the ship he so loved. But their loss was not without purpose. Kasey Moore and Earl Henry are heroes who helped hasten the end of one of the bloodiest wars ever fought. Without the bomb, America would have been forced to stage a land invasion of Japan that would have cost hundreds of thousands of American lives. The author of this article is the grandson of a man who fought in the Pacific Theater, who could have easily died in such an invasion. I may never have been born without the bravery of Knoxvillians Kasey Moore and Earl Henry. For that, I am forever grateful.

USS Indianapolis Memorial

At the north end of Canal Walk in Indianapolis, IN, you’ll find the national memorial for the USS Indianapolis, which was torpedoed and sunk by Imperial Japanese Navy submarine I-58 on July 30,1945. The memorial was formally dedicated in 1995, 50 years after the sinking. The memorial commemorates the 1,195 crewmen, of which only 316 survived the sinking, dehydration, exposure, and shark attacks. The death toll of 879 was the largest single disaster at sea in U.S. Navy history.