This article was written by former Mare Island Museum Librarian Barbara Davis and it first appeared in the museum’s newsletter in 2013.

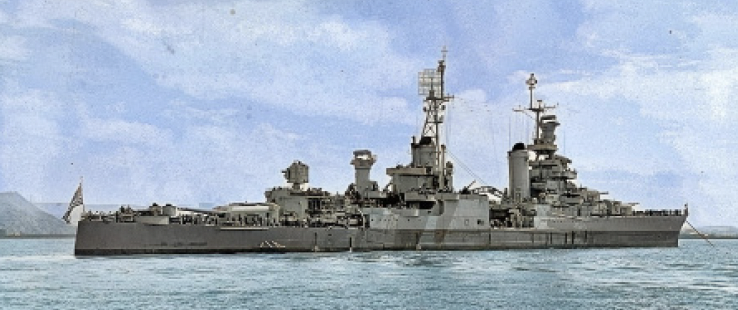

On 14 February 1945 The USS Indianapolis had just rejoined Adm. Marc A. Mitscher’s fast carrier task force which was planning an attack on Tokyo to cover the invasion of Iwo Jima. After participating in that raid and another on Kyushu, Indianapolis was sent to Okinawa where she spent seven days pouring 8 inch shells onto the beach defenses. American ships were constantly being bombarded and the Indianapolis shot down six planes and damaged two others. But on 31 March her luck ran out and the ship’s lookouts spotted a Japanese fighter headed toward the bridge. The ship immediately began firing, but it was too late.

The enemy pilot, before crashing into the water on the port side of the ship, was able to launch his 500 lb. bomb from a height of 25 feet and it went through the deck, into the mess hall, down into the berthing compartment and through the fuel tanks before crashing through the keel and exploding in the water underneath the ship. Two huge holes were torn in the keel and flooded nearby compartments. Nine crewmen lost their lives and 29 were injured. Listing to port she headed to a salvage ship for emergency repairs, but it was discovered that her propeller shafts were damaged, her fuel tanks were leaking and her water distilling equipment was inoperative. She was sent across the Pacific under her own power to Mare Island for more extensive repairs than could be accomplished at a forward operating base. She arrived at Mare Island on 1 May 1945. Expecting to be here about four months, Capt, Charles B. McVay, a third-generation Navy man, had his new wife join him and many of the other men got leave and went home to see their families.

While at Mare Island there was a major turnover in personnel, many of them new sailors and some “90 Day Wonders” (officers) were also assigned to the ship. McVay was more than a little concerned about the inexperience of this crew. Would they be ready when the ship was scheduled to sail? Work on the ship commenced and while here she received a new port quarter, new radio and radar equipment and new fire control mechanisms. When the repairs were completed, she was to be sent out for a week of sea trials to make sure she was ready to return to duty. Meanwhile in another corner of Mare Island Naval Shipyard in an inconspicuous building labeled 627A, another mission was taking place. Mare Island had been chosen by the scientists at Alamogordo to pack the parts for the A-bombs for shipment to Tinian Island. MINSY was selected because of its success in packing cargo for the South Pacific without it being damaged in shipment, but more importantly, without damage from humidity.

The A-bomb components had been flown from New Mexico to Hamilton Field in Novato, CA, just across San Pablo Bay from MINSY. For that voyage, an irreplaceable part of the shipment was packed in a 15 foot crate and kept under the watchful eyes of two Army officers, Major Robert Furman, an engineer, and Capt. James Nolan, a radiologist, both of whom were identified as “artillery officers.” After off-loading the components were brought to Bldg. 627A. Project Alberta was the code name for the transporting of the materiel to Tinian Island and it is believed that Mare Island was involved in two parts of this project.

One was the Bronx Shipments which were the irreplaceable parts of the bombs and were sent on the Indianapolis. These included a uranium projectile which would be shot from the “gun” at a “target” piece of uranium (flown to Tinian from Wendover Field in Utah) which would create the critical mass and cause the explosion, as well as the fifteen foot crate previously alluded to. The other part of the project was the Bowery Shipments and these were the replaceable parts of the bombs such as special lenses and the “pumpkins.” Pumpkins were high explosive bombs in the exact shape of the Fat Man bombs which were to be used to train the crews and get them used to the ballistics of dropping these bombs.

The pumpkins had been designed by the Manhattan Project as non-nuclear replications of Fat Man bombs. (Only one uranium bomb was built because of the difficulty and time required to manufacture enough of the fissile uranium for Little Boy type bombs.) A total of 486 pumpkins were built, some live and some inert. They were used by the crews and bombardiers training at Wendover, as well as the crews flying from Tinian Island who were using live, high explosives versions. 49 were dropped on Japa-nese cities, one went into the ocean and two were on aborted missions. The Tinian crews had the restriction that they could not drop the high explosive pumpkins on Hiroshima, Nagasaki or any of the other cities which were determined to be possible targets for the actual A-bomb.

There is speculation that they were called pumpkins because they were painted a pumpkin orange. However, all existing photos show them painted with the same primer as all other bombs. Items packed as part of the Bow-ery Shipment were likely shipped out of Port Chicago, a support unit of Mare Island, after they had been lightered there from MINSY.Eventually Mare Island packed five shipments which went to Tinian by water. The first two batches were critiqued upon arrival at Tinian. A lieutenant was flown 5500 miles from Tinian to San Francisco in order to directly inform the supervisors at Mare Island of the condition of the shipments upon arrival on Tinian. Batches three, four and five were most important, in fact so important, that those first two had been for practice only. Meanwhile the work on the Indianapolis was accelerated by around –the-clock work by shipyard workers.

Four months of work were completed in two and half. Capt McVay was told he had one day to complete his shakedown cruise, not a week. For some unknown reason 2500 life jackets were put aboard during re-supply, more than twice the number required. It would later turn out to be a blessing. She sailed out on 14 July and returned on 15 July. On her return McVay was told to report to San Francisco and meet with two officers – Admiral William Purnell and Captain William (Deak) Parsons, the associate director of the Manhattan Project and the man who super-vised the shipments from Project Alberta at Mare Island.

Parsons briefed McVay that he was carrying a secret cargo and it would have a major impact on the war effort. He said to McVay, “ You will sail at high speed to Tinian where your cargo will be taken off by others. You will not be told what the cargo is, but it is to be guarded even after the life of your vessel. If the ship goes down, save the cargo at all costs, in a lifeboat if necessary. And ev-ery day you save on your voyage will cut the length of the war by just that much.” McVay was then sent back to Mare Island to bring his ship to Hunter’s Point Shipyard in San Francisco where the cargo would be loaded.Once again Maj. Furman and Capt. Nolan accompanied the cargo. They thought the ship looked magnificent, but had not been told that it had long been speculated that her center of gravity was too high and she would capsize almost immediately if she took a clean torpedo hit.

Their accommoda-tions were like being on a luxury cruise as they were berthed in the flag lieutenant’s cabin where the bucket, with half the fissile uranium in the US worth $300 million, had been bolted to the floor. The 15 foot long crate, with all the screws countersunk and sealed carefully with red wax so no one could attempt to open it, was lashed to the deck and guarded by a Marine guard at each corner 24 hours a day.Speculation among the crew was rampant – some thought it was a secret rocket, others that it was Rita Hayworth’s underwear and still others were betting it was gold bullion to bribe the Japanese to end the war. It actually carried the integral components of Little Boy. Eventually McVay sent for Nolan, who explained to the captain that he was not an artillery officer but a medical officer, and he could assure the captain that cargo did not contain anything that would be dangerous to the crew or the ship. (The “target” uranium was being flown to Tinian and without it there could be no “explosion.”)

The Indianapolis set sail the morning of 16 July at 0830 with an intermediate stop at Pearl Harbor for refueling. Averaging over 29 knots for the first stage (a record) she got to Hawaii on 19 July. Five hours after arriving she set sail for Tinian 3300 miles away and arrived there on 26 July where her cargo was offloaded. Indianapolis was then ordered to Guam. She arrived on 27 July and received orders to head to Leyte in the Philippines for two weeks of training prior to joining Task Force 95 which would be a major element in the invasion of Japan scheduled for 1 November. Before leaving Guam on 28 July, McVay requested an escort. The request was denied.

On 30 July the Indianapolis was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine. In less than twelve minutes she capsized and sank. Many of those extra lifejackets ended up floating and were used by men in the water. Many men were horribly burned or had broken bones and died within hours of sinking. But the worst was yet to come – within hours sharks appeared and their numbers would increase over the next five days. It is believed that sharks killed at least 200 sailors.

At Leyte on 1 August, no one noticed that the Indianapolis had not arrived. Had someone noticed – searches would have occurred within a day of the sinking, but no one went looking. On the fourth day, 2 August, just by chance, a Navy pilot on a routine anti-submarine patrol noticed the men in the water. He radioed their position and soon planes arrived. The crews threw out their own life-saving gear to the men in the water and then watched in horror as more sharks arrived and attacked the men. Eventually a PBY Catalina flying boat made an unauthorized landing in the open sea and while receiving information from planes flying overhead was able to pluck 56 sailors, some near death, from the water.

They had to wait for surface ships to arrive for medical care and the PBY was eventually sunk as she was unable to fly again. By 3 August, 321 men had been plucked from an area of several hundred miles. Capt. McVay and his group were among the last to be rescued. Four of the men died; there were 317 survivors from a crew of 1196. To add insult to injury, Capt McVay was court-martialed and found guilty for hazarding his ship by failing to zig-zag, though the Japanese submarine commander testified it would have made no difference if he had.

His punishment was to lose 100 places in grade, making promo-tion impossible. He remained in the Navy until 1949, but never again served aboard a ship. Burdened by the death of his wife, the death of his favorite grandson and hate letters from families of crew members who had died, he committed suicide in November 1968 by shooting himself on the front steps of his home in Connecticut. At the first crew reunion his former crewmen told him they wanted to clear his name. His response was “I got what the regulations called for – I got what I deserved.” However, they continued to fight for years to have his record cleared. Finally, in 2000, Congress passed a joint resolution acknowledging the wrongful conviction of Capt McVay. Though the resolution was signed by President Clinton, only the Navy could exonerate him. On 13 July 2001, the Secretary of the Navy, Gordon R. England, took that action. The Navy also awarded a citation to the Indianapolis and her crew for having successfully delivered the A-bomb components to Tinian.

Congressional Gold Medal

On July 30, 2020, the United States Congress awarded the Congressional Gold Medal—its highest civilian honor—to the Final Crew of the USS Indianapolis CA 35 during a ceremony at the Indiana War Memorial. The virtual ceremony was held on the 75th anniversary of the loss of the vessel. USS Indianapolis preparing to leave Tinian after delivering atomic bomb components.

After the sinking, the crew “fought to stay alert, to look after each other — literally to hold on for dear life,’’ “Those who perished in the water gave our nation the ultimate sacrifice … but the true legacy of the Indianapolis was secured before those torpedoes struck,’’ Senator Mitch McConnell said. “Her crew turned the tide of the war. So to her crew members who are still standing watch: Your Congress and your nation say thank you.”